Wystawa czasowa

29.10.2010 - 17.01.2011

The Wawel Royal Castle, the western wing of the castle

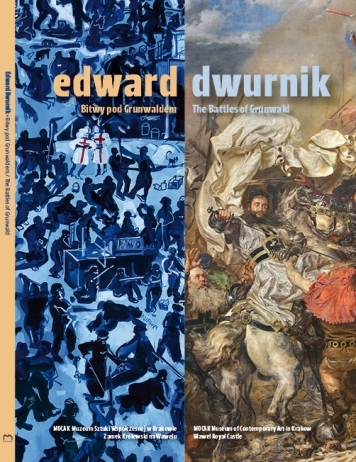

The Battles of Grunwald

Edward Dwurnik is one of the few contemporary painters who take on board historic themes. History is not the sole motif in his work; it comes up, however, in no fewer than 200 paintings and in a few thousand drawings. Dwurnik is clearly addicted to history. He is aware that it was history that shaped him, deformed him, demoralised him, dignified him and did many other things to him on which he had no influence at all. Historical events and monuments (such as The Palace of Culture and Science) are for the artist signposts of memory. They also function as public signs of remorse and moral obligation. One has to remember that Dwurnik was born in the year of the Ghetto Rising and has experienced in his own life all the acts of historical violence that befell Poland from that moment onwards. All these events appear in Dwurnik’s work; each worked into a cycle, each dealt with in differently from the artistic point of view.

Maria Poprzęcka, The Polish Scene after the Battle *

On the other hand, the differences between the two Battles of Grunwald can be multiplied to infinity, beginning with size. Dwurnik's canvas, while large, is significantly smaller (“It has the dimensions of Guernica,” the artist admits modestly). Matejko thrusts the viewer into the midst of the crush of battle. Dwurnik, in line with an old battle-painting tradition, offers a bird's-eye view. Matejko's painting is strikingly colorful. Dwurnik paints his Grunwald with “tar and ink” (as Józef Czapski described his paintings under martial law ). There is no delectable display of glistening armor, rich caparisons, embroidered satin, or flashing swords. There are no heroes with historical names. The anonymous, shabby figures lay into each other with clubs (and crosses). Without enumerating all the differences, we might also note some observations regarding gender. “The Battle of Grunwald is a world without women. An ideal image of a homosocial community,” writes Ewa Toniak. Dwurnik's battle is not same-sex. Several female figures wander among the brawling men. Are they camp followers? No, rather the sisters of Florence Nightingale in white smocks with big red crosses on them. In the fervor of battle, they have lost the high-heeled shoes that litter the field here and there. These nurses are not, indeed, rendering aid to anyone, but as red-and-white spots they punctuate and unify the black and dark-blue plane of the image. Additionally, they bring in the always desirable red-and-white accent. Continuing with the theme of gender, we might also suppose that the presence of women relieved the artist of the necessity of painting horses, which are eroticized in Polish culture and treated as interchangeable with women. Many other animals, however, are loitering here, and not only the mongrel dogs that always feature with Dwurnik. In the center, we see two small elephants (mascots?). Next to the condors waiting for their carrion is the profile of a disconcertingly large white dove of peace.

*fragment of a text from a publication to accompany the exhibition