The open Gallery Anna Maria Potocka and Rafal Bujnowski talk about art on billboards

MARIA ANNA POTOCKA: This issue’s theme is pop culture, understood as a way of thinking that makes culture and art more easily and more widely accessible. However, what is at stake here is not a physical or institutional availability but rather an ideological one. You have contributed a lot to this cause. First, you deprived your works of any elitism or exclusiveness, in a way stripping painting as such from its snobbish uniqueness, and then you let art loose on the streets...

RAFAŁ BUJNOWSKI: These are two different, albeit interconnected, matters. I did actually go through a period in which I reproduced paintings and prepared editions. I think it was because it was so easy to make a painting in this way. Sometimes creating such an ‘edition’ piece took me five, maybe ten minutes, so in order to give my work some meaning I had to make more copies. Remember that it was in the era of young capitalism. To each action there had to be a reaction; I just answered the demands of the time, right? I think my billboard action sprang in part from this kind of thinking because this is when first advertising billboards started to crop up. And I was interested in their potential as a public space for presenting paintings. Now I hate them.

By setting up a gallery out on the streets, on billboards, you wanted to express a certain kind of rage; to cut yourself off something?

I think you partially answered your own question. I was angry at the elitism, at this respectability, especially when it comes to Krakow’s artistic circles, at their supposed immunity. Before, art used to be different, maybe it was able to take it. I think that in 1998, when I set up the Open Gallery, art had different needs. It preferred the street to the salon.

How did it happen that you, a rather private and introverted person, decided to go out on the streets and set up a billboard gallery?

I probably wanted to overcome my on weakness. They say that clowns are the gloomiest people in the world.

How long did you run the gallery?

Almost four years, until 2002.

How many exhibitions did you organise?

I do not know exactly, I never kept inventory. Probably several dozen.

Really? And nobody ever made a serious monograph out of it?

No.

Do you at least have any documentation left?

Yes... But it is unfortunately quite poor. It was still before digital cameras, so I have a large box of old pictures, some of them glued together.

Which artists presented their works in your gallery?

Those whose wanted to, my friends, mostly people from Krakow. But sometimes also others, like Wojtek Kucharczyk from Katowice.

How did they work on an exhibition like that?

Some artists were sticking things to the billboard, some painted on the spot, at night.

There was only one billboard?

No, three, sometimes even four, all presenting different works.

So you displayed various artists simultaneously?

They displayed themselves and one author created pieces for all billboards. But to be honest, there were no rules. If someone wanted only one billboard, they were free to do so.

Did you choose these artists or was there complete freedom?

No, maybe not complete freedom. First the artists told me about their project, about what they wanted to do. When the idea was not good and I suspected that the billboard might stay blank, the project was dropped. If the idea was solid and the project was reasonable, it was put into action.

But for the most part these billboards were actually good in terms of artistic quality. At least those that I remember; I did not get to see all of them. In fact I was not even aware there were so many.

Of course, since good artists participated in the project.

Did the sheer fact that you had to paint something out on the street, on a billboard, without any hope for a profit, eliminate the less brilliant artists?

Maybe.

And how did you gain access to those billboards?

One of them was mine. We just assembled a metal sheet together with some friends.

Illegally?

Legally.

So you got permission to do it?!

Yes, from an energy company, because we hung it on transformer box at the corner of Dietla and Krakowska Streets. I rented two other billboards free of charge from AMS.

Did you run the gallery all by yourself or did other members of the Ladnie Group also become involved? Was it your idea?

Yes, this idea was actually mine. Marcin Maciejowski was responsible for the magazine, ‘We Wtorek’.

And what was Wilhelm Sasnal responsible for?

He co-operated both with the gallery and the magazine. Although he was much more involved in the magazine.

And what about the rest? Firek? Or maybe already at this point he did not take part in this action?

He did, he did. Everybody prepared something, they contributed to this whole work. They put together exhibitions in the magazine for instance.

How many of your own exhibitions did you display in the Open Gallery?

Several, maybe more than ten. Not so much exhibitions as posters. I did not count; there was no need.

Mostly paintings?

Not necessarily. I also glued some prints to be torn away. Pop culture. Those were original linocuts signed in pencil.

By whom?

By the author, in this case me.

How many were there?

Several dozen. They were glued on one billboard to be torn away.

An what did they represent?

Some objects, items of everyday use.

I remember combs and VHS cassettes...

Since they were left there to be torn away, they quickly disappeared. I think people ripped them off, maybe because they thought it was ‘funny’.

Maybe they ended up on the market?

I do not think so. They probably got destroyed since the paper was of poor quality.

So nothing about this gallery appeared in print? A type of an overall catalogue?

No, nothing like that.

And ‘We Wtorek’ did not publish reproductions of these billboard exhibitions?

Only a couple or so, and that only as photocopies.

Well, it reflects well on the gallery. It did not want perpetuity; it enjoyed the temporary. And what did you take out of it artistically?

For me it was a verification of sorts. It afforded an easy and quick way of checking whether something has a sort of outside meaning. I presented my works to completely random, hard-core viewers. Such a lesson in billboard realism. I could see what gets sprayed on in words such as ‘you fucking cunt get the fuck out of our hood’ and what stays intact, what is respected. You know, the people of the streets know how to appreciate some things. This was a kind of a survival camp. No professor ever agreed to being displayed on the street.

Did you ask them?

Of course, almost all of the ones I had contact with.

And no one ever said yes?

No. Even though I tried to encourage them by saying things like, ‘But Professor, we are all waiting for you to join our gallery, you know’.

You said before that thanks to the gallery you managed to get insight into social relations.

Not get insight because I am not that insightful, but understand a little, yes. I think many painters could use such a lesson. The canvas will take just about anything but what is really interesting is how the painting affects people, how it manages to hurt someone or flatter them. It is cynical in that advertisement, shown on the billboards every day, works in the same way.

This attitude would be cynical if it referred to paintings displayed in galleries and museums. But out on the street, the rules are different. What counts is rather the rights of other people. When you enter public space you have to weigh what you are saying and who you are saying it to.

But such an awareness, such knowledge may result in some sort of cynicism. I think.

How often did you pass by these billboards?

I lived in the neighbourhood so I watched them all the time.

But did you come closer, did you watch people?

To see what they are doing or how they are reacting? No. I only checked for comments of destructive interaction because people warned me about those. Mostly they warned me about people from the streets, like graffiti painters, because they formed a strong circle, much stronger than the artistic milieu. I even met with their guru and the spray king accepted the Gallery.

What happened to the work after the exhibition?

It was covered by its follower.

So all artists new they were creating a doomed work?

Absolutely.

It was always painted or glued directly on to the board?

Yes.

Did the whole billboard change or only some fragments? Because sometimes several artists shared the same board.

Usually people wanted to take the entire hoarding. Even though they were huge, two metres by five. Billboards were just starting to be introduced in Poland. I am talking about the commercial ones. They were new to all of us. Only later did the avalanche start. Now it is past breaking point. It is like a plague. We should announce a state of emergency and regulate these billboard images. But back then it was a novelty. Everyone liked billboards, nobody was against them like today, when many people are starting to fight them.

As a painter, you probably suffer from heightened visual sensitivity and this must be quite difficult to you.

I treat those billboards as noise, squeals and high tones.

Why did the gallery end?

It just died naturally of old age.

Old age? After three years?

Yes.

Artists did not want to participate anymore or did you just get bored? Or maybe the distance between the exhibitions increased and everything just died down from sheer lack of energy?

All those reasons combined. This is when the AMS Gallery started out and professionals invaded on the street. It ceased to be the place for us.

What did you learn when running the gallery? Apart from...

...the way in which image can work? I am not sure whether it gave me something tangible. Maybe I gained some confidence. After all, it consisted in public appearances and displays.

But what did you gain from presenting others?

Friendship, pleasure of being a part of a group, a sense of community. Such things. And besides, the participation of other people meant that they accepted the idea of painting on the streets.

Did you treat it as more of an artistic or curatorial activity?

It was artistic.

So in a certain sense you were creating a piece of art entitled ‘Open Gallery’.

You could say so. It was my original way of expression.

But it was not your explicit intention right from the start? Do you only begin to see it in this way now?

Intention for it to be art? It is always better to avoid such intentions.

Did the artists who displayed their pieces in your gallery realise that they were becoming a part of your work?

No, mostly because I was not aware of it. But I did drill holes in those billboards and I did fix the metal sheet to the scaffolding, so I was in fact the author of the frame. At the same time, the Open Gallery was a part of the Ladnie Group’s programme; it was one of the forms in which it operated and an emanation of its energy.

When did the Group end?

After the Academy. It was a student association, just like the gallery; it had this random structure. Afterwards someone called it pop banalism. In the evening you painted what you had for breakfast. This could be the definition of pop banalism for the purposes of our conversation.

Where in Krakow did the Gallery billboards hang?

At the corner of Dietla and Krakowska Streets there was my own billboards, the one we had to screw on. One of those rented from AMS hung towards the end of Dietla Street near the Vistula, the other one was on Krakowska Street. All bore the Gallery logo. As you can see, we started out big. The logo presented a man sketched like on road signs and inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing.

Who prepared the logo?

I did, when I was a student at the faculty of graphic arts. I still have some logo stencils. It was fantastic in that I was so overzealous, I was naive enough to think I could change the world. Students have something like this in them.

It is not naivety, just young selflessness. Nobody thought about career, fame or money. Everything was done out of spontaneity and ideological needs. Before the onset of capitalism, also adult artists expressed such attitudes. And maybe you are right that today, in our capitalist reality, a behaviour like this could be called naivety. Did the press somehow react to the Open Gallery, did they write about you or record your activities?

There was something but unfortunately I did not file it in my archives.

So how was it perceived? That some children were just playing around or rebelled youth were launching an artistic revolution?

That Academy students were doing this and that...

It should have been super interesting for journalists. They had a chance to write a great deal about social, non-artistic issues. Did they try to talk with you?

No, thank God. I remember that ‘Machina’ did mention the Gallery at some point. It was when I met Michal Kaczynski and Lukasz Gorczyca. Michal used to write a column in ‘Machina’ and mentioned the Gallery.

You thank God that journalists did not interview you. So thank you that much more that you agreed to speak with me.

You are writing about ‘pop culture’, so these pictures from ten years back may still have some meaning. Thanks.

Rafal Bujnowski (born 1974) – painter, graphic artist, author of videos, installations and artistic actions. Graduated in graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. Between 1995 and 2001, he formed the Ladnie Group and co-edited the ‘We Wtorek’ magazine together with Marcin Maciejowski, Wilhelm Sasnal, Marek Firek and Jozef ‘Kurosawa’ Tomczyk. Between 1998 and 2002, he run the Open Gallery, displaying various works on billboards in Krakow.

-

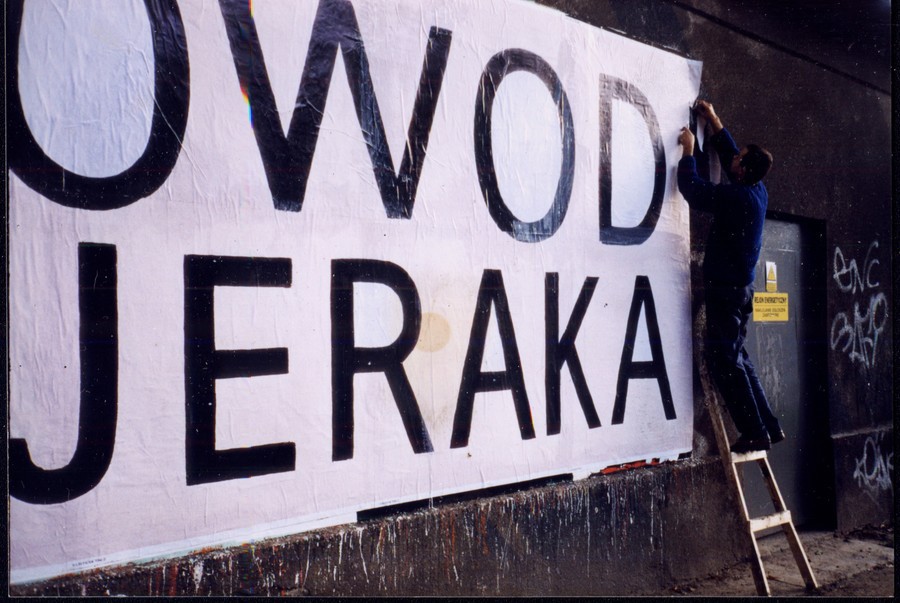

A work by Rafal Bujnowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

A work by Rafal Bujnowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

-

A work by Jadwiga Sawicka, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

A work by Jadwiga Sawicka, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

-

A work by Marcin Maciejowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

A work by Marcin Maciejowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

-

A work by Rafal Bujnowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

A work by Rafal Bujnowski, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

-

A work by Wilhelm Sasnal, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive

A work by Wilhelm Sasnal, Open Gallery, picture from the OG archive