Memory loss on the borderline Sebastian Frąckiewicz

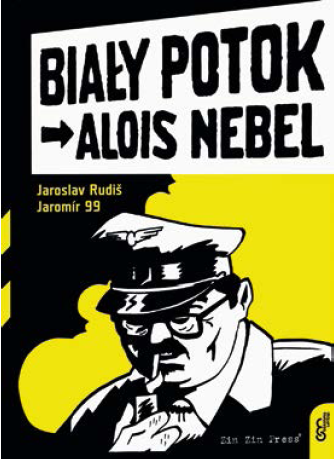

Trilogy Alois Nebel about which we can be envious towards the Czechs, is a graphic novel about a simple railway man from the province. Jaroslav Rudiš and Jaromir 99 decided to sweep off from beneath the carpet the Czech-German history and in this fascinating way present the history of Sudetes, like in Hrabal’s gawęda (1)

This story, similarly to many other Czech stories, begins at a bar, and precisely at a bar in Žižkov in Prague (familiar place, isn’t it?). A graphic, illustrator and a drawer Jaromir 99, writer (at that time known as the author of The Sky under Berlin) and a Germanist Jaroslav Rudiš get together for a beer. Jaromir 99 and Jaroslav Rudiš come from the borderland. Jaromir from Jesenik, close to the Polish Głuchołazy, and Jaroslav was born in Turnov, close to Polish Liberec, the pre-war capital of Sudetic Germany where currently an installation/sculpture of David Černy is scaring tourists. The installation/sculpture is presenting a table with a cut off head of Konrad Henlein who was a pre-war leader of Sudetic Germans who were collaborating with Hitler. Jaroslav and Jaromir find common ground because of similar origin and fascination of history. However, Jaromir is distant to the idea of his friend-writer who wants his main character to be a railway man like Jaroslav’s grandfather. Jaroslav, because of his sight defect, couldn’t become one. That’s why he decided that his childhood dreams need to come true in the form of a comic strip. Indeed, in brief, they manage to finish Alois Nebel, one of the most famous Czech comic strips in Europe.

Something of Burns, something of Hrabal

Jaromir 99 gets slightly irritated when his graphic style, based on a strong contrast of black and white, a game with chiaroschuro and the reduction of dispensable details, are compared by everyone to Sin City by Frank Miller. Allegedly, the inspirations were different, and precisely the comic strips by Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns. Both names belong to two famous American artists of the independent comic strip world: masters of narration about human emotions, disabilities, and madnesses. In brief, the masters of the moral comic strip or if somebody prefers, the graphic novel.

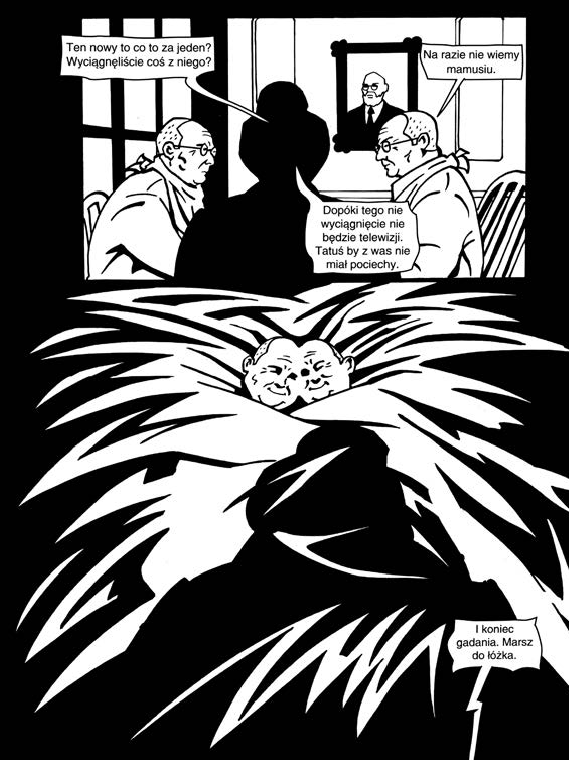

Moreover, the comic strip, Alois Nebel, is rooted in the traditional Czech literature. There is the Czech province, simple but kind people, the local “thinkers” who love telling anecdotes while sipping a beer. Besides, the entire graphic novel is composed of anecdotes, seemingly insignificant but constituting the detailed landscape of Sudetes.

“The characters of the comic strip are peasants, simply »locals«. They classify everything according to their categories. Their centre of the universe is the nearby bar. I think that it is typical of the East- Central Europe mentality. A similar mentality can be found in Sudetes, in Slovakia, and in Hungary.

Every peasant is self-righteous and thinks that he knows everything about the world even though he or she has never crossed the line of his or her town. That’s why they don’t like Praguians, nor those from Ostrava, nor from Warsaw. We are just fascinated by this Czech rusticity. Certainly, we don’t identify with it but we do know this way of thinking. Thanks to the fact that we managed to portray these people and their imagination about the world, Alois Nebel gained many fans” said Jaromir 99 when a couple of years ago for the first time the authors came to Poland for a meeting with their readers.

The most important “local” is the title Alois Nebel, a simple railway man who only once visited Prague. He spent his entire life at the little station at Biały Potok. Interestingly enough, the world of switches and timetables has never become boring to him. He just adores this job.

Certainly, he is a self-taught philosopher (he has got plenty of time for reflection) and his entire life will make him think about the railway.

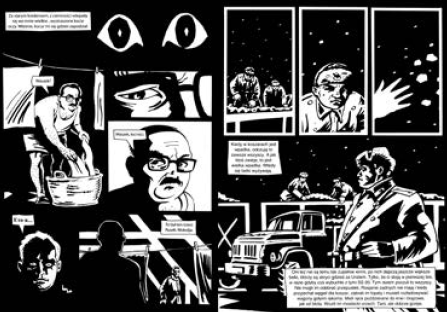

“A human being is not in a better or worse position than a train which is arriving at the railway station because neither a human being nor a train doesn’t have influence on which track they enter. There is somebody else who controls that,” says our character in the second part of the trilogy, The Main Station. In spite of what it seems, Nebel is not a regular railway man. Time after time in front of his eyes, from the secret fog, trains of the past emerge: both those with Jews to Auschwitz and those with Germans expelled from Sudetes. Due to this, he ends up at a mental hospital.

Would Hayden White like Nebel?

In the famous poetic of historic writing, Hayden White presents his recognition of Maus. I am almost certain that he would like Nebel for effacing the boundaries between history and literature, for the questioning of the phenomenon of historic memory and most of all for the different way of presenting history of a given country. Not from the point of view of Prague, but of Biały Potok, forgotten by God and people, not from the point of view of an important historic figure but a provincial.

What is the most interesting in Nebel, is, not so sophisticated, but a convincing metaphor in the form of a fog and trains of the past. We can certainly interpret the fog as peculiar “losses” of the collective memory from all the unpleasant events of the “locals” were to be eliminated. All the more reason, some of them were cynical collaborants.

In the recently published Miedzianka, Filip Springer presents the lives of German inhabitants of Kupferberg who were transported after the war beyond Odra in scandalous conditions. It shows Poles in a quite unfavourable light. Nevertheless, in comparison to scenes which we can see in Aloise Nebel, the descriptions from the Springer’s book are not drastic. In the Czech comic strip, certain Wachek trades with Germans first and then, after the war, he joins the Communists, he takes a revenge on the Germans, the same ones with whom he used to drink before. Interestingly enough, Waszek, a colloborant and a typical despicable beast is one of the main characters. As the authors ascertain, the Czechs who are distant towards their history, they really like their most popular smarty-pants from Białe Góry.

“Wachek is such an archetype of a little Czech pig who knows how to find himself in any circumstances. He is not a reflection of one specific person. However, these kinds of people were present under each regime” says Jaroslav Rudiš. He assures that there isn’t anything surprising in that because Czechs like autostereotypes, contrary to the “serious” Poles.

Czech versus Polish historic comic strips

The biggest paradox is that in this “serious” Poland where history is treated so deadly serious and there are still many problems with the losses of the collective memory, nobody publishes serious historic comic strips. And even if sometimes they pop up, such as Achtung Zelig by Krzysztof Gawronkiewicz and Krystian Rosiński, they don’t gain popularity and they are not recognized. Although, in the case of Zelig, similarly to Nebel, history has been metaphorized. In the album of the Polish duet, Holokaust has been presented as an action of cleaning up Poland of Polish animals (and precisely of cats), and the main characters are excluded from the excluded, i.e. Jews. Maybe if Achtung Zelig was relased in Czech Republic, it would have had a better reception. Nevertheless, when Rosiński and Gawronkiewicz are giving an example of a similar way of thinking about the history in comic strips, such as Jaroslav Rudiš and Jaromir 99, the majority of Polish historic comic strips are insipid images from a crib sheet shallowing history: Solidarity, The Poznań 1956 protests, The Pacification of Wujek. Most usually they are prepared for solemn anniversaries. They don’t even have ambition to become an art form. In the meantime, Alois Nebel has received its second life becoming a movie adaptation. The comic strip has also met with a good reception in the German media. At the end we can just envy the Czech Alois Nebel and its completely different way of presenting history in a comic strip. Let’s hope that in Poland a paper version of Aloise Nebel will be released because the comic strip with the most famous railway man of our southern neighbor is a totally different thing than the album. The Polish plot is very visible there. Even a single fact that we have “our” priest officiating the marriage to a homosexual couple or “our” mafia dealers. Maybe if it was published, we would find out that it is iconoclastic comic strip which asperses our country. However, probably Czechs won’t understand that. Nevertheless, as it is known after the scandal with Chopin, scandal is a good tool to promote a comic strip in Poland. While waiting for the “scandalous” version of Aloise Nebel, it is worth familiarizing with the equally excellent album version of the trilogy.

(1) Translator’s note: a story that belongs to a kind of Polish epic literary genre, stylized as an oral tale).

Sebastian Frąckiewicz (born in 1982) – a cultural journalist and comic strip critic, author of Emerging from the ghetto. Talks about comic strip culture in/ Wyjście z getta. Rozmowy o kulturze komiksowej w Polsce (2012). From 2007 to 2012, he was running the section with comic strip reviews in “Przekrój”. He also published in the pages of “Lampa”, “Newsweek”, “Film”, “Aktivist” and on portals of Filmweb and dwutygodnik.com. Currently, he is working for “Polityka”, “Tygodnik Powszechny” and “Take Me”. He is running a blog about comic strips: komiks.blog.polityka.pl/