Graphic novel Anachronism or future? Lukasz Gazur

„There was a moment when people more or less stopped reading poetry and turned instead to novels, which just a few generations earlier had been considered entertainment suitable only for idle ladies of uncertain morals. Someday the novel, too, will go into decline - if it hasn't already. […] It's not too soon to wonder what the next new thing, the new literary form, might be. It might be comic books. Comic books are what novels used to be - an accessible, vernacular form with mass appeal - and if the highbrows are right, they're a form perfectly suited to our dumbed-down culture and collective attention deficit” wrote Charles McGrath in 2004 in the pages of “The New York Times”.

Even though the graphic novel gains the recognition of critics and the readers’ hearts, there are still discussions held not only on the topic of the definition but the history of the graphic novel as well. The boundary between the comic book and the graphic novel is fluent; therefore it is easy to overlook it by accident. Is it worth using this term then?

The birth of the graphic novel

For the first time, the term was used already in the 30s of the last century by Lynd Ward. He created the novels using the technique of wood engraving. But the real birth of this movement took place 40 years later. In 1978, Will Eisner published A Contract with God which gave the beginning to the trilogy carrying the same name. The artist was already recognized in the world of comic books. His stories in images were published in press and his detective novel The Spirit was cinematized. It wasn’t enough though for the American author of Jewish decent. Eisner dreamt of describing the place where he was raised, Dropsie Avenue, a legendary, now immigrant street of New York. That’s the way the first part of the trilogy was born, a fictional story amassing all the memory crumbles. In its pages, one may find the pious Jew, Frimme Hersh, who loses his beloved daughter. At that moment, he breaks the contract with God and he becomes a tenement house-owner. You may also meet a singer who was found in the crowds by an opera diva who was past hers time. Unfortunately, the singer instead of appearing at the concert halls prefers to reach for the bottle. As a result, he is not able to take advantage of the chance given by the destiny.

In the second part entitled, A Life force, Eisner presents himself as Jacob Shtarkah. We will see the reflection of the Great Crisis of the 30s, the leftist currents gaining popularity among the elites, the birth of Hitlerism and among all of that, the existential character’s quest.

By the way, it’s worth mentioning that Robert Crumb allegedly called this very part of the trilogy a masterpiece. It was acknowledged that the author of the graphic novel has an insightful look in, similarly to Henry Roth’s one, and a social verve as John Dos Passos.

In the third book entitled Dropsie Avenue, Eisner plots and portrays the characters of the inhabitants of the legendary avenue over time, describing the next waves of immigration. The Dutch, English, Irish, Jews, African Americans, Latin Americans, all of the immigrants bring their customs and social norms. The world changes and the former social habits are subject to disintegration; a cultural mix gives birth to a new quality.

History has found a voice in images

Will Eisner knew that his work will move beyond the norms of a classic comic book which in the 70s was only associated with sensational stories or fictional list of records of superheroes. He had to find a different term describing what he created in order to emphasize this narration distinctiveness. He chose the term “graphic novel”. The PR action turned out to be successful.

The same year (1978), Raymond Briggs published a book The Snowman, a cartoon book about a boy, a snowman and the Cold War. This preview already causes that this volume should be treated differently than a regular comic book. But it didn’t go this way. The author of works sold in the amount of 3 million exemplary is still considered to be an author of comic books for children even though his Gentleman Jim or When the Wind Blows are novels which cannot be really defined as a classic comic books. There are plenty of allusive games, subtexts referring to reality, not necessarily in an obvious way, even the two mentioned novels, the stories of an employee of a public restroom and his wife. Their knowledge about the world comes mainly from tabloids and TV. They dream of a better life, they would like to become the middle class to an extreme degree but the result is poor. Provided that Gentlemen Jim is “only” a novel about the ambitions of the working class, When the Wind Blows goes even further and becomes a game with reality. Everything because of the historic background. The work was created in 1982 when the nuclear rivalry between the USA of the Reagan’s presidency and the USSR of the Leonid Brezhnev’s presidency and his successors terrified the world. That was when the British Government published a flyer Protect and Survive. The result of this publication recalled War of the Worlds by Orson Welles. The content of the flyer terrified the society. It was advised not to panic after the attack since nobody has a chance to survive. The main element of the flyer was the instruction how to find the corpse of our relatives if one survives a bit longer. The reflection of those moods can be found in the Briggs’s novel. However the comedy changes into a drama because the explosion really takes place and the characters still believe in the government and the recommendations from the flyer.

Obviously this comic story has been recognized as an event, a thing about the propaganda which ploughs the brains of citizens and it became classic.

As it is visible, the graphic novel’s year of birth is correct but there is a problem with fatherhood: Briggs or Eiser?

Does it need to be a graphic novel?

The successors went the same way, for instance Art Spiegelman, a Jew of Polish descent, in his famous Maus. It’s a story about Holocaust where different nationalities have faces of specific animals. Maus will go beyond the poetic of sensational stories by means of cartoon telling. Art tries to understand the experience of his father, a prisoner in Auschwitz. After the war, Władek was considered a stingy, rude and suspicious man. He behaved this way towards both strangers and family members. Father-son talks on which Maus was based on turned out to be a terrifying testimony.

From the beginning, the novel in images by Art Spiegelman evoked a lot of controversies. The idea of presenting events from the times of extermination in a form of a comic book was criticized and seen as not very serious by many critics.

In Poland, this comic book was published only in 2001, nearly 10 years after awarding Spiegelman with the Pulitzer Price. The reason of such late release of the work was the accusations of anti-Polish motifs: Spiegelman presented Poles as pigs what outraged not only the critics but also a big part of the public opinion. Also displaying in certain cases Poles as anti-Semites or as camp foremen in Nazi camps caused numerous protests. Spiegelman underlined that considering it this way, this novel should be considered “anti-Polish” and “anti-Semite” to the same extent. He also showed Jews collaborating with Nazis during the Second World War. The character of the father is soaked by the stereotypes of a stingy and distrustful Jew.

This novel, dressed in black and white, raw in its form and its topic, i.e. presentation of a tragedy of his family caused that, with time, Maus was considered a graphic event, appreciated by the mentioned Pultizer Prize.

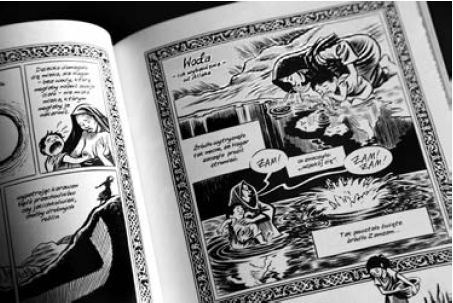

Blue pills by Frederik Peeters reverberated in the world. He told the story about his relationship with a woman, an HIV transmitter, and about building a family with her and her infected son. In 600 pages of Blanket,s Craig Thompson drew a story of his growing up. Recently, his Habibi was released which treated about pursuit of survival at all costs and about longing. It’s one of the most significant publishing houses of the previous year which will certainly go down in history. It’s most of all a graphic novel about the clash of Europe and the world of Islam, about how many things divide it and unify it at the same time. It’s a story of a relationship between Dodola who was given in marriage in her childhood, afterwards selling her body to caravans in the desert and Zama, a little dark skinned boy. The destiny unified them on a slavery market and then separated them. She will be put in a sheikh’s harem whom she will entertain day and night (not only in the alcove), he will become a eunuch, and therefore there will be a wall of physical limitations and desires between them which will not be able to be fulfilled.

The plot situated “somewhere in the Arabic countries”, without precising the place and time of action, within the assumption, it was supposed to become a universal parable. With time, Thompson started to enrich it with references to history, science, philosophy, to cite legends and folk stories, weave parallels between the Bible and Coran (not by accident the cover of this volume resembles the saint books). On this fascinating tracking of differences and similarities, there is no frontal worlds clash. There is interfusion and sometimes noiseless crossing of the borders. Everything is shown with precision and great care of every detail. The Arabic writing becomes almost ornamental.

Constant retrospectives and returns to lost plots do not only dynamize the story but they almost force it to become a mystic story. Intriguing! However, it is important to add that at some moments Thompson got caught on a stereotypical perception of the Arabic culture.

Where does it lead?

We can fish out a few graphic novel discriminants from this graphic panorama. Ambitious topics, often referring to what is socially or morally at the time “hot”, go far beyond the frames of sensational stories. It’s also often a work exceeding the amount of a dozen or twenty couple pages typical of American comic book publishing houses. It often contains many autobiographical elements or descriptions of historical events or currently discussed issues. Nevertheless, in the times of effacing the boundaries, is it still necessary to apply the PR actions in order to sell more ambitious cartoon stories? It seems that the division is artificial and the young intelligence without disgust reaches for comic books. Let’s recall the example at Vistula river. It was loud about Życie codzienne w Polsce 1999-2001 / Everyday Life in Poland 1999 2001 by Wilhelm Sasnal published in 2001. Probably the most famous Polish contemporary painter told the story of his life with his wife Anka. The unbearable lightness of being clashes with the discrete charm of the artistic bohemia. And everything inscribed in the Polish reality. Unfortunately, pregnancy is endangered, the scholarship lost and due to lack of money they need to move from Krakow to Tarnow. By the way, we find out how much a roll costs at a store and that doctors like gossiping about each other.

Paweł Dunin Wąsowicz called this image story a generational novel and the editor promoted it as “the favourite comic book of the young intelligence”. It speaks for itself.

Łukasz Gazur (born in 1983) – a journalist and an art critic. Connected to “Dziennik Polski”. He published, among others, in “Przekrój”, “Tygodnik Powszechny”, “Arteon”, “Exit”, “Sztuka.pl – Gazeta Antykwaryczna”. He is an author of texts for Małopolska. Znaki w przestrzeni./ Małopolska. Signs in the Universe.