Good God, Poor God – Małgorzata Rejmer

Małgorzata Rejmer (b. 1985) – writer, PhD student at the Institute of Polish Culture, University of Warsaw. In 2009, she published her debut novel Toksymia, which earned her a nomination to the Gdynia Literature Award in 2010. She writes a blog Rejmer: skraje i skrawki on zwierciadlo.pl. Her second book, Bukareszt. Kurz i Krew was published in September 2013.

Good God, Poor God

This word, like a little stone, like a little piece of glass – ‘writer’ – just doesn’t come out of my mouth.

I often meet people that are on their way somewhere, under a bus shelter, on a marshrutka, on a train. This people are willing to tell you as much of their story as can possibly fit into their mouth. They know they are about to disappear. Sometimes they ask, ‘and what do you do?’. This is like a sort of a variation on the theme of ‘who are you?’.

I tell them I am a person that writes. Basically unemployed. Because writing, my version of it, is just too indefinite. No discipline, no schedule, sometimes even no pleasure. There is more of not-writing than writing. Emptiness, and then, on this barren land, sudden floods of words that flow together with water when I wash the dishes or peel potatoes. Someone else’s words, some pegs on which I hang the raw slices of ideas. And then – cutting phrases and tossing them away. Rather than in a laboratory or a library, it’s like working in a dark, dirty kitchen, where you cannot invite anyone and cannot possibly successfully clean the floor.

A writer, this brazen bastard, a con man by definition, in the collective imagination a shrivelled four-eyes or a withered artist of life, an alcoholic of course. Meanwhile, for me, a writer is first of all a clerk, laboriously gathering phrases onto a pile, subtracting, adding, checking if all was done correctly. A remorse-ridden clerk, always unfulfilled, usually weighed down by the nonsense of the writing pursuit, saddened by the scale of the limitations.

Still, people think that writing offers an ersatz of freedom. Phrases just come out spinning from under your pen, produced by a crank-operated device fuelled by inspiration, which is why writers should focus on gathering experience, on talking with prostitutes and bums, on drinking and debauchery. When writers come back home after several days of partying, they find a dozen pages of text already sitting on their desks. Inspiration did its best.

Meanwhile, this illusion of freedom falls down on writers, just like on all other people, only for a fleeting moment. And it disappears after a short while, chased away by the burden of obligations, routine and diligence. Writers, like all other people, need to keep themselves in order at all times. Be careful not to plunge into addiction. No to lean out too much from their towers, lest they smash their heads against the ground. Keep an eye on their hearts so that they don’ break.

Six years ago, after I had written a story about the USA, an editor from a certain newspaper asked me to write an article that was to become the key to my career. So I went out of the house, found my heroes, recorded their words – and then, while writing, I realised how easy it was to invent something. I will make this gentleman say this and that. I will make this lady all new. And then we will have a situation like that.

The editor sat down to read my text. He circled everything that was good. Everything that was good was also fabricated. Please correct the rest, said the editor.

That was when I realised I could not be a reporter. You can’t start writing the truth by lying.

I decided that since I was so good at cooking stuff up, I should concentrate on fiction. Two years later, I started writing Toksymia, vanishing from life for seven weeks. In the evenings, my boyfriend would take me out for a walk along a square-shaped trajectory. He said they were penalty walks, a forced eviction from the textual world out into the real world. Cars were too loud, buildings too high, faces suspect and inhuman, and I felt like a prisoner that left the safety of her cell.

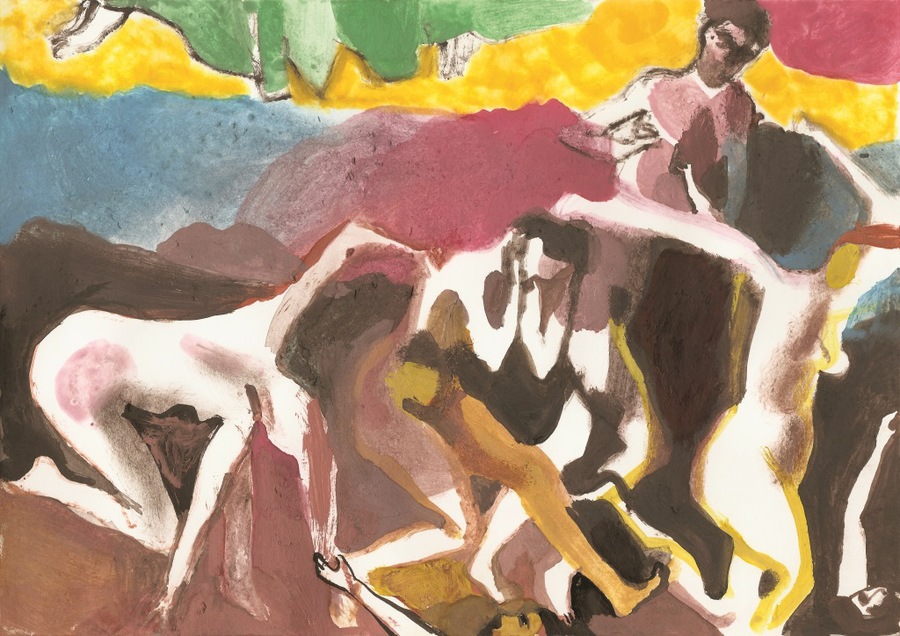

When I was writing, I was euphoric. I have never felt as free as in the time when I plunged into the novel. In my own world with my own people. This group of misshapen people that I controlled. I was very mean to them. I left some of them stranded at the very last moment, while some could enjoy a kind of a happy end. To them, I was a malicious, insidious God.

But being God has this advantage that God, as probably the only being in the world, is free. I was a poor, trifle god, and that only for a brief moment. But I tasted freedom.

Although Toksymia is full of stories that someone told me, no one has any doubts that it’s pure fiction. Meanwhile, some time had passed, I went to Bucharest, and I kept getting little gifts in the form of stories. People reconstructed the past from small events that etched themselves in my memory. From covering the toilet seat with paper in order not to get a bladder inflammation. From walking past toy shops where you couldn’t buy any toys, but emptiness, lacking, bitterness and sorrow were all free to take.

Writing the Bucharest reportage had nothing to do with the freedom I had felt during Toksymia. I had to stick to the facts and meanings imposed by other people. I owed the truth to my characters – their truth, the truth they had invented in order to live and to survive.

When writing prose, I can imagine the life of a fictional character, from birth to death. If I want to, she will become a puppet or a metaphor. It was really different when I had a seventy-year-old woman sitting in front of me, spending long hours to reconstruct the map of her life. She knows when she made mistakes. She knows when the system caught her at the throat, refusing to let go. She knows she was a victim of politics, and that all her liberty consisted in freedom to roam a blind labyrinth. I listen to her story and am suddenly petrified by the thought that now we both can grasp the expanse of the 70 years of her life. All the unknown quantities have been identified, and still the equation doesn’t make any sense. I see myself reflected in her eyes – what will be my story when I am her age? What gift will my writing freedom bring me in the perspective of a whole lifetime? Will it be a feeling of space or emptiness? Fulfilment or failure?

When I write, my ego triumphs, strutting around like a peacock. I leave a little piece of myself in each of my characters – feeling particular satisfaction whenever I create egoist or deceitful personalities. But when I am working on reportages, I can no longer count on this prose-bound freedom. The protagonist is more important than myself. My ego is cast aside. I become just an ear that listens. A hand that writes. And still, I sometimes am tempted to rewrite the lives of my characters, like a true writer would. I want, finally, to become a good God, one that rejects fear and failure.