Wystawa czasowa

07.03.2026 - 14.06.2026

Alfa Gallery, MOCAK Library

Annette Kelm: Speak, Volumes | Tomy, przemówcie

-

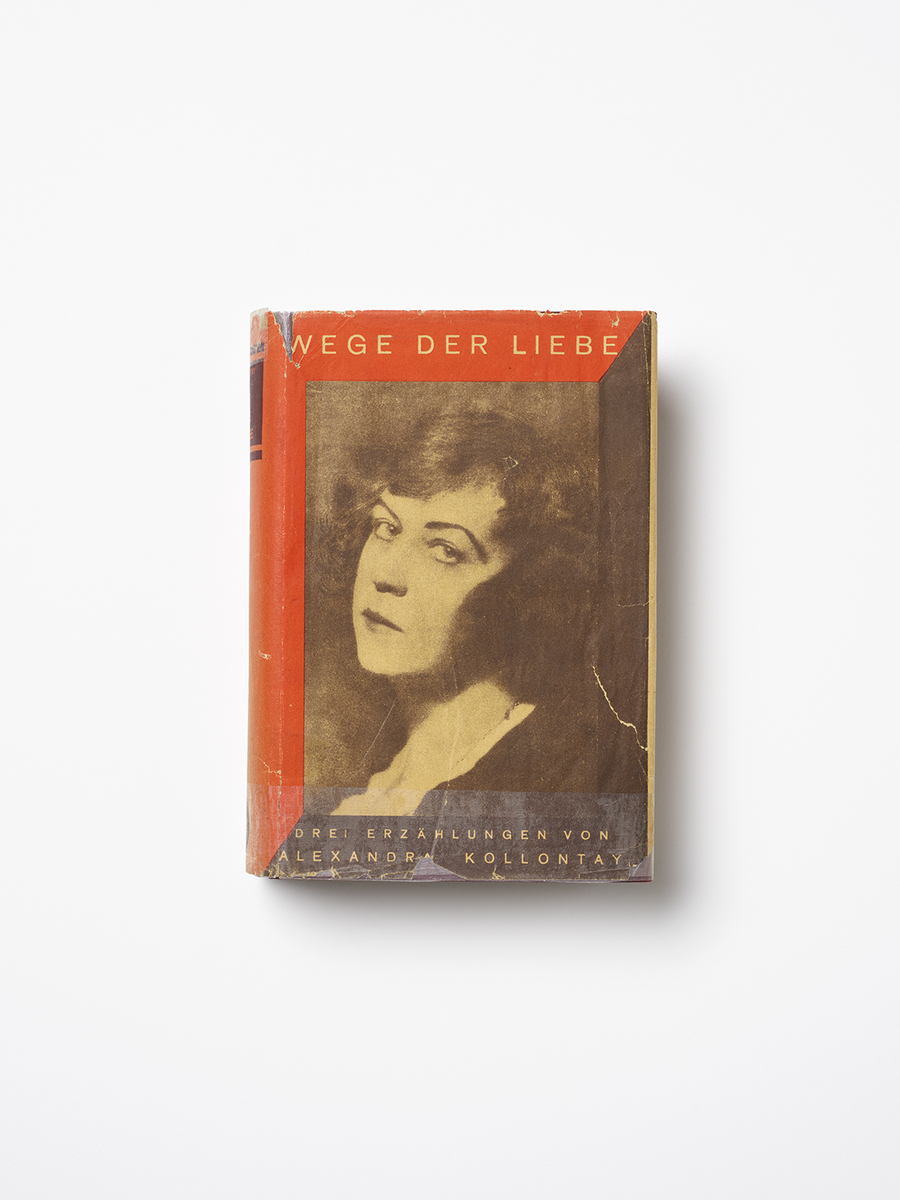

Annette Kelm, Alexandra Kollontay, Wege der Liebe. Drei Erzählungen: Die Liebe in drei Generationen, Schwestern, Wassilissa Maligyna, 1925, Malik-Verlag A.-G. Berlin, autorisierte Übertragung aus dem Russischen von Etta Federn-Kohlhaas, Einbandgestaltung John Heartfield, 2021, from the series Die Bücher, archival pigment prints, 71.5 × 54 cm, courtesy the artis and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul

Annette Kelm, Alexandra Kollontay, Wege der Liebe. Drei Erzählungen: Die Liebe in drei Generationen, Schwestern, Wassilissa Maligyna, 1925, Malik-Verlag A.-G. Berlin, autorisierte Übertragung aus dem Russischen von Etta Federn-Kohlhaas, Einbandgestaltung John Heartfield, 2021, from the series Die Bücher, archival pigment prints, 71.5 × 54 cm, courtesy the artis and Esther Schipper, Berlin/Paris/Seoul

Curators: Krzysztof Pijarski, Anna Voswinckel

Co-ordinator: Mirosława Bałazy

The exhibition is part of the Krakow Photomonth

Annette Kelm’s Die Bücher and Travertinsäulen Recyclingpark Neckartal

In the photographic series Die Bücher, Annette Kelm depicts covers of around one hundred individual volumes – first or early editions of books that were banned, blacklisted and many of them publicly burned by the Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945. The “Action against the Un-German Spirit” of the German Student Union that found its culmination in the infamous book burning on the Opera Square (today’s Bebelplatz) is often seen as emblematic of the nation-wide campaign, initiated by the NSDAP and supported by organizations such as the SA and the Hitlerjugend. The book burnings were meant to end the intellectual pluralism of Weimar culture. Libraries and publishers received instructions to remove banned books from catalogues, reading rooms, and shelves. In Poland, too, after the occupation by Nazi Germany, libraries were systematically destroyed as they were considered repositories of knowledge and bearers of Polish identity.

Kelm stages each of these books frontally, on a neutral white background, lit evenly, and cast with a soft shadow. Portraits, one might say: the cover becomes the face, the photograph itself a persona, embodying the author, the graphic designer and the content of the book. They become uniquely present, and yet not entirely ours: their interiority remains out of our reach. What Kelm accomplishes is double-layered: on one side, she gives renewed visibility to works, authors and designers who were violently excluded from public life – books and authors erased from libraries, bookshops, the cultural consciousness – in that way her works form a counter image to the visual narratives created by the perpetrators. On the other hand, she reflects on the status of the book-object and the photograph-object: how representation, form, presence, and materiality interact in the arena of memory, loss, and salvage.

In this context, Annette Kelm invites us to view books as a distinct category of objects. Objects imbued with agency that carry ideas across generations and cataclysms. As discrete, bound samples from the whole of human knowledge, they invite discussion, incite love, provoke hate, go missing and are found again, with all kinds of delays. Viewed in such a light, Kelm’s work is not about death and destruction, but rather resilience and survival. But also about the inevitable entanglement between the psychical and the non-psychical, between human memory and its externalizations, in books and objects and flows.

We are witnessing the closing of the Gutenberg Parenthesis, the period where print remained the dominant form in which thought could survive individual psychical organization, death. And while the fate of the Timbuktu manuscripts in 2013 reminds us that the burning of books does not safely belong to the past, in contemporary digital culture, where data flows obscure material objects, ideas are no longer destroyed primarily by the fire of erasure, but by a paralysis of the user: suppressed not by silence, but by algorithmic modulation, the blinding fabrication of content, where surveillance is not replaced, but weaponized to fuel a reactive machinery of distraction, of hyperabundance, including the onslaught of AI-slop. This library reminds us that to thrive, thoughts and ideas need a medium, some kind of support, a binding, not to be swallowed by noise.

Indeed, Annette Kelm knows that not only books can speak volumes, they are not the only objects to hold ideas. In Travertinsäulen Recyclingpark Neckartal, she photographed a row of travertine columns nestled between what is now a recycling facility and a waste-to-energy plant on the outskirts of Stuttgart. They were originally commissioned in 1936 by the City of Berlin at Lauster quarry in Stuttgart, and intended for a monument to the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini for the Adolf-Hitler-Square (Theodor-Heuss Square today), which was planned to be part of Albert Speer’s world capital “Germania.” Because the war had taken a different course to that envisioned by the Nazis, the columns were never picked up and remained at the site. After the war, Lauster bought the columns back from the City of Berlin and erected them in front of the quarry as advertising. Fourteen 15-meter-high columns still stand there, now surrounded by the postmodern architecture of a waste incineration plant. By documenting them in their surroundings with her camera, Kelm makes these “antiquities” release the ideas that have been inscribed in them nearly a hundred years earlier.

Kelm’s work asks us to engage differently with material culture – how the book, as object, becomes a bearer of collective memory, a portal to forgotten or suppressed discourse. And by photographing these books as objects, as images, she also asks how we look – how we remember – how these objects mediate absence and presence. A rhythm, sometimes elating, but often menacing, as in the strong chords of the travertine columns, as it is not always the ideas one would wish to have survived.

Interestingly, this focus on mass-produced objects as bearers of interiority, of ideas, of survival, also addresses a question posed a long time ago by Susan Sontag while pondering the over-production of images as a force devouring a sense of reality and access to experience. Like other authors of her time, she was aware of the double role photography played in advanced industrial society: as a spectacle, and object of surveillance, directed by the capitalist idea of consumption. Her proposal of a way out of this double bind was an “ecology of images” as a kind of “conservationist remedy”: while there are always more images to consume, and while each might offer some knowledge of the world, it will play a greater and greater part in determining on which we decide to focus as sources and points of reference, for better or worse. Die Bücher are, from this perspective, a strong candidate, at the same time leaving us with the crucial question: how can we look without seeing exclusively, how can we remember, and not look away? How to preserve plurality, while focusing on the essential? Annette Kelm’s project presents a model of such a plurality, something as precious as it is fragile. Something it is worth caring for.

Annette Kelm – was born in 1975 in Stuttgart, Germany. She lives and works in Berlin. Annette Kelm studied at Hochschule für bildende Künste, Hamburg. She received numerous awards and prizes, among them Camera Austria Prize (2015); Preis der Nationalgalerie, Audience Award (2009); and Art Cologne Prize for Young Artists (2005). Annette Kelm’s photographic oeuvre offers a unique outlook onto the socio-cultural history of the material world. The artist uses a vast array of motifs as vocabulary to address specific moments in this history, whether it is the commodification of design objects, various forms of political critique or value systems such as money and finance. Kelm’s exhibitions gather images of floral sculptures, landscapes, portraiture, photographed buildings, and ephemeral objects of all scales. Meticulously picked, the artist’s subjects enter in collision and contrasts where the objective converges with the subjective, the every-day encounters the historical, and the impartial becomes political. Her practice draws from conventional studio photography techniques: employing a large-format camera and depicting her subjects in front of a backdrop. The arrangements that the artist sets up at her studio are often playful, retain an experimental character or are seemingly captured glimpses of time. Kelm’s distinctive approach to the photographic medium has made her a prominent figure of contemporary photography in Germany and worldwide.

Anna Voswinckel – a curator based in Berlin, specialising in contemporary photography and lens-based media. She has a background in visual arts, cultural, and gender studies. For two years from 2023, Voswinckel has been the curator of the exhibition programme at Camera Austria in Graz, during which time she has realised group shows such as the two-part project Exposure/Double Exposure, as well as solo exhibitions with Alexandra Leykauf, Anouk Tschanz, Ana de Almeida and Huda Takriti. In 2020, she co-directed the 10th edition of the Fotograf Festival Prague with Stephanie Kiwitt and Tereza Rudolf, entitled Nérovny terén/Uneven Ground. She was co-founder and art director of the international art and literature magazine Plotki – Rumors from around the Bloc, which was published in Berlin, Warsaw, and Prague between 2000 and 2010.

Krzysztof Pijarski – a visual artist/researcher/educator/curator. He is associate professor at the School of Form / SWPS University, and member of the Visual Narratives Laboratory at the Film School in Lodz (https://vnLab.org), which he co-founded and co-directed in 2019-2024. A big part of his work at the vnLab was focused on the Interactive Narratives Studio, where he worked on developing webdocs and other narrative and archival interactive pieces, especially in the transmedial space. Out of his engagement with bound content, he initiated the PubLab Collective around his vision for web publications as an evolution of the printed book. His interest lies above all in exploring convincing visual forms of thinking: visual essays, atlases, analogies. As an artist, he focuses primarily on the aesthetic – that is, sensuous – dimension of the epistemological, political and ethical, creating visual archaeologies of institutions and discourses, biographies of people and things. He has published books on Allan Sekula, Michael Fried, Thomas Struth, and Zofia Rydet. He is a founding editor at Widok: Theories and Practices of Visual Culture (https://pismowidok.org).